On June 2, 2013, the Sunday edition of the New York Times ran a major investigative

article by Elizabeth Rosenthal called “The

$2.7 Trillion medical bill”, with the subtitle “Colonoscopies explain why

the US leads the world in health expenditures”. It is a damning article about

the US health care system, and the fact – fact

– that our costs are much higher than those in other countries but our outcomes

are often worse, and large portions of our population are not even covered.

Of course, it is not all colonoscopies. Yes, the average cost for a colonoscopy in the US

is $1,155 compared to $655 in Switzerland (for example). And many cost much

more; in the first paragraphs of the article we hear about charges of $6,385, $7,563.56, $9,142.84 and $19,438

-- “…which included a polyp removal.

While their insurers negotiated down the price, the final tab for each test was

more than $3,500.” ! But the graphic at the top of the article compares US prices

for other common procedures with those of other first-world countries: Angiogram $914 US, $35 Canada; hip replacement $40,364 US, $7,731

Spain; MRI $1,121 US, $319

Netherlands; Lipitor (atorvastatin, a

drug to treat high cholesterol) $124 US, $6 New Zealand.

But colonoscopies

provide a good example for why we pay

so much more for procedures – and it is not because they are of higher quality:

“Colonoscopies… are the most expensive

screening test that healthy Americans routinely undergo — and often cost more

than childbirth or an appendectomy in most other developed countries. Their

numbers have increased manyfold over the last 15 years, with data from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggesting that more than 10 million

people get them each year, adding up to more than $10 billion in annual costs. Largely

an office procedure when widespread screening was first recommended,

colonoscopies have moved into surgery centers — which were created as a step

down from costly hospital care but are now often a lucrative step up from

doctors’ examining rooms — where they are billed like a quasi operation. They

are often prescribed and performed more frequently than medical guidelines

recommend.

The high price paid for colonoscopies

mostly results not from top-notch patient care, according to interviews with

health care experts and economists, but from business plans seeking to maximize

revenue; haggling between hospitals and insurers that have no relation to the

actual costs of performing the procedure; and lobbying, marketing and turf

battles among specialists that increase patient fees.”

Welcome to the

world of for-profit health care. Where the principle of “maximize profit”

determines what health care institutions do. Where “what we do” (our “product”)

is health care, but we prefer to do it on those with really good insurance.

Where we adjust our charges to maximize the difference between what it costs us

and what we are paid. Where the rules set by insurers or government with the

aim of regulating costs are seen as challenges to be gamed for maximum profit.

The movement of colonoscopies – and many other procedures – from doctors’

offices to “surgi-centers” is a great example. If performing colonoscopy in an

office was unsafe, moving to a surgi-center might be a good idea, but there is

little evidence that it was. Moreover, the increased price for performing a

procedure in such a center far exceeds the increased cost of doing it there;

the reason for the move is not

patient safety, but taking advantage of a loophole to be able to charge more.

Rosenthal’s

article is a long one; it extensively documents both the high cost of health

care in the US and the reasons why it is so high, which are rarely related to

quality. This is illustrated by an article published in the Times a few weeks earlier, “New Jersey hospital has highest billing

rates in the nation”, by

Julie Creswell, Barry Meier, and Jo Craven McGinty. “The most expensive hospital in America is not set amid the swaying palm

trees of Beverly Hills or the luxury townhouses of New York’s Upper East Side,”

they write, but Bayonne Medical Center, in Bayonne, NJ, where the average

charges are 4.1 times the national average

charge, not to mention what Medicare will pay. For some services it is much

higher: “Bayonne Medical typically

charged $99,689 for treating each case of chronic lung disease, 5.5 times as

much as other hospitals and 17.5 times as much as Medicare paid in

reimbursement. The hospital also charged on average of $120,040 to treat

transient ischemia, a type of small stroke that has no lasting effect. That was

5.6 times the national average and 23.6 times what Medicare paid.”

How can they get

away with this? Who will pay them so much? After all, if I can buy a Chevrolet

for $25,000 at one dealer in town, why would I pay $75,000 for the same car somewhere

else? Ah, but health care is different. For one thing, you might be sick when

you have to find a hospital to care for you, and you might live in Bayonne! Of

course, Medicare will only pay what Medicare pays, but if you have most types

of commercial insurance (not to mention, of course, if you are uninsured), it

is another story. To guard against excessively inflated charges, most insurers

have contracts with providers (hospitals, doctors, etc.) that determine how

much they will pay for a procedure or treatment of a disease. This saves the

insurer money. In addition, in order to encourage you to go somewhere that they

have negotiated these lower rates, “in-plan” hospitals, they pay a lower

percent of the cost – and you pay more – if you go “out of plan”.

And it is

precisely this effort to control costs that many for-profit hospitals (like

Bayonne) have turned on its head to generate greater income. They have gone

“out of plan” for all health plans. This means that when you show up in their

ER, or are admitted, you have a higher co-pay, and co-insurance charge, and the

insurer pays them more money. Which is why the insurer doesn’t want you to go

there, and you might (once you knew this) not want to go there either. Except,

of course, you’re sick, and you live in Bayonne, and it is the closest ER. Talk

about gaming the system!

Spending & Coverage (2010)

|

France

|

U.S.

|

Total health spending per capita

|

$3,974

|

$8,233

|

Government health spending per capita

|

$3,061

|

$3,967

|

% uninsured

|

0%

|

15.7%

|

Health

outcomes (2010)

|

||

Life expectancy at birth (2011)

|

81.3 yr.

|

78.7 yr.

|

Infant mortality per 1,000 births

|

3.6

|

6.1

|

Costs

per episode (2012)

|

||

Doctor’s office visit

|

$30

|

$95

|

Hospital day

|

$853

|

$4,287

|

Angioplasty

|

$7,564

|

$28,182

|

Appendectomy

|

$4,463

|

$13,851

|

Childbirth delivery (normal)

|

$3,541

|

$9,775

|

Hip replacement

|

$10,927

|

$40,364

|

Heart bypass

|

$22,844

|

$73,420

|

Tests

(2012)

|

||

Abdominal CT scan

|

$183

|

$630

|

Angiogram

|

$264

|

$914

|

MRI

|

$363

|

$1,121

|

Name-brand

drugs (30-day prescription, 2012)

|

||

Cymbalta

|

$47

|

$176

|

Lipitor

|

$48

|

$124

|

Nexium

|

$30

|

$202

|

Sources:

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and International

Federation

of Health Plans. |

||

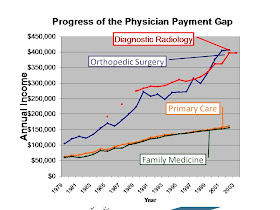

I have implied

that much of the reason for the high cost of health care in the US is the high

cost of procedures. Frankly, that is true. It is why procedural specialists

make so much more than primary care physicians. This is why decreasing the

difference in income potential for proceduralists and primary care doctors

would be good for everyone and save money: there would be more people doing

primary care and less incentive to do unnecessary procedures. Consumers Report, in its July 2013

issue, has an article on the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) movement,

which seeks to achieve the “triple aim” of higher quality, greater patient

satisfaction, and lower cost. The article, “A doctor’s office that’s all about you”, also addresses the high cost of care in

the US, comparing it specifically to France, which spends 11.6% of its GDP on

health care and “…is generally

acknowledged as having one of the world’s best health care systems.” Needless

to say, the comparison is not flattering to the US, which spends 17.6% of GDP

on health care.

Richard Wender, MD, a leader in US family medicine,

commenting on the “Colonoscopies” article, says “Using health care as a driver of corporate economics as opposed to a

public good is the fundamental cause of our medical inflation.” Lee Green,

MD, an American who is now a family medicine leader in Canada, adds “Having practiced most of my career in the

US, and now practicing in Canada, the contrast is quite evident. The US health

care system is not designed to get you the care you need, it is designed to get

you the care that someone can make a profit giving you. If you're poor and

uninsured, that's none - no matter how much you need it. If you're

well-insured, it's a lot - including quite a bit you don't need, and even some

that is harmful.”

This is crazy. We know the problem, and we know the solutions. All we need

is the will to implement them. Maybe this continued exposure will generate it.

We can hope so.