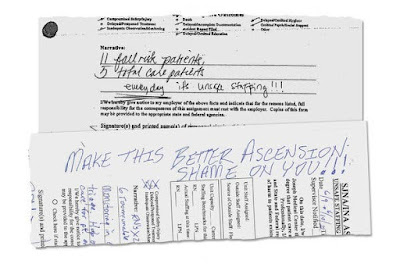

The New York Times’ latest exposé on the despicable actions of large, ostensibly “non-profit” health systems, ‘How a Sprawling Hospital Chain Ignited Its Own Staffing Crisis’, examines Ascension Health, one of the largest such systems in the US. It is definitely worth reading, although you may want to try deep breathing first. Ascension owns hospitals over a wide area of the US, mainly in the Midwest, and took a bow in 2019 when it “was trumpeting its success at reducing its number of employees per occupied bed, a common industry staffing metric”, saving $500M! Unfortunately, cutting the number of employees to bare bones limited the quality of care available to patients. And when the COVID pandemic hit, and occupancy rates skyrocketed, they were woefully understaffed – except that the woe was experienced by the patients who sought, and to one degree or another, received care in those hospitals. It was and remains a disaster. Among the impacts cited in the article: at one hospital “there were so few nurses that psychiatric patients with Covid were left waiting a full day for beds, and a single aide was on hand to assist with 32 infected patients”; at another “Chronic understaffing meant that patients languished in dried feces, while robots replaced nursing assistants who would normally sit with mentally impaired patients.” Think about that patient being your parent! Disgusting? Upsetting? Dangerous? How about downright evil?

But, you might think, the cost cutting was necessary. After

all we

read about hospitals that are on the brink, are barely surviving, needing

government bailouts to keep serving their communities. Oh, wait, those are different

hospitals. Those are rural safety net hospitals. Ascension has $18 Billion in

the bank. $18 Billion! In a “non-profit” hospital system! Boy, I’m sure

that those C-suite execs who oversaw that got big 7-figure bonuses! And now?

With that much in the bank, I doubt they are going to suffer much just because

people are getting terrible care and dying in their hospitals.

So how are these systems non-profit? The Times does a good summary:

In exchange for avoiding taxes, the Internal Revenue Service requires them to offer services, such as free health care for low-income patients, that help their communities.

But…

The Times this year has documented how large chains of nonprofit hospitals have moved away from their charitable missions. Some have skimped on free care for the poor, illegally saddling tens of thousands of patients with debts. Others have plowed resources into affluent suburbs while siphoning money from poorer areas. And many have cut staff to skeletal levels, often at the expense of patient safety.

Oh. That doesn’t sound so good. And, to be sure, Ascension is far from the only “non-profit” hospital chain to behave in this manner; most of the big and “successful” ones do so. The West’s Providence Health System, the focus of a previous Times exposé and post on this blog ("Non-profit" hospital systems behaving worse than for-profits: No end to the scams”, October 1, 2022), ironically started by a group of nuns to care for the poor and underserved, also gets coverage in this article.

There is so much evil here it is hard to know where to start. Certainly, a key part is running networks of institutions ostensibly created to heal the sick and injured (“hospitals”) as if they were manufacturing businesses and employing au courant management strategies designed for manufacturing, such as “just in time” supply chains and cutting staff down to the bone. This is absurd; hospitals, to be effective, to be able to meet regular seasonal changes, not to mention disasters or pandemics, need to have excess capacity at all times. Running “lean and mean” is wrong on many levels. It is exploitive of the staff, and indeed puts staff in the position of providing poor-quality care to their patients, compromising their professionalism and commitment; the testimonies of the nurses at Ascension are the most damning part of the report. It makes it difficult to impossible to gear up in times of need. And it um, kills people. You cannot have a potential staff of on-again-off-again health care workers to be employed just when needed “just in time”. If you could, if such excess capacity existed in the society, it would be yet another sign of perversion, of oppressing people and their families and communities to make more money – profit for “non-profits”.

Another way that this is, to put it gently, inequitable, is

described in the Times article: cutting back on services in high-need-but-low-income

communities and reallocating them to wealthier neighborhoods. And, of course,

emphasizing and marketing high profit-margin services (cancer care,

orthopedics, neurosurgery, cardiac interventions). Again, a morally bankrupt strategy to meet not the

health needs of our country but rather the dollar desires of a board of

directors!

So what do I have to add to the excellent coverage given to this issue by the NY Times? They even call it “Profits over Patients”, which it is. I think I can give the problem a name that the Times will not: Capitalism. Capitalism is the problem. And it is not just any capitalism, it is not the capitalism of mom-and-pop stores or small businesses or making a reasonable profit, it is the capitalism-run-amok, it is the capitalism of anything-for-a-buck, full-speed-ahead, don’t-care-who-gets-hurt, bigger-is-better, I-want-to-be-a-billionaire-too that we have seen increasingly over the last decades. It is the capitalism that Noam Chomsky calls “gangster capitalism”, but in many ways what these folks do worse than what gangsters do, because it threatens not only people but all of our society. Sure, a gangster may threaten or even kill you. These systems are designed in a way that will kill thousands! But you know what? That is capitalism, that is the end point of capitalism. That is the Gordon Gekko, greed-is-good, result of capitalism that is not only unfettered by government regulation (especially with the elimination of many of the best parts of the New Deal) but that is actively enabled by a government that is willing to let private companies take all the profits when they make them and bail them out when they lose. And it is arguably even more evil that the hospitals described in the Times article are large “non-profits” which behave exactly like for-profits except that they don’t pay taxes! Who would have thought I’d be arguing for for-profits? Well, I’m not; they actually providing even worse care for the community because there are almost no regulations governing what they do. But at least they pay taxes.

So what can be done? A great deal actually.

- Ban for profit corporations, or any entity controlled by private equity, from health care delivery. Yes, hospitals, but also clinics, urgent care centers, nursing homes, etc.

- Require not-for-profit entities to behave like

non-profits are supposed to, with community benefit being the SOLE criterion by

which they are judged. Do not allow building of facilities, expansion, or the

dissolution of “product lines” except when it can be demonstrated that this

will benefit the health of the overall community. Not allow “we’re moving

into/building into this prosperous expanding suburb because, you know, they

will need health care” if it means there will be inadequate resources to serve

the people in the most needy, sickest, and poorest communities. No

cannibalizing inner-cities to feed wealthier suburbs. And while it may not be

possible to directly regulate the income (salary and bonuses) of C-suite

executives of non-profits, the requirements should ensure that they cannot make

loads of money and build huge reserves ($18 billion! Come on!) If they won’t do this, tax them

- ·Ensure that the communities most in need, especially in rural areas, have their needs met on a case by case basis. The absurd Hobson’s Choice the federal government is offering rural hospitals, crystallized in the headline of the article cited in the second paragraph, “A Rural Hospital’s Excruciating Choice: $3.2 Million a Year or Inpatient Care?” must be changed so that each hospital, and the larger community it serves (sometimes geographically enormous) gets support for what it needs, inpatient care, outpatient care, and usually both.

Even better, while eliminating private for-profit ownership, discourage misbehavior by non-profit owners by creating and implementing a single payer health system, such as Medicare for All, which as the sole payer would be able to with and regulate these health systems for the benefit of the health care of the people of our country.